Scott Skillman is an Indiana attorney in his 34th year of practice. He spoke about Ida Finkelstein during The Bridge Project ceremonies Sept. 26 at Allen Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Terre Haute. Historian Crystal Reynolds told George Ward’s story during the same event. View the full program on Facebook.

On February 27, 1901, Rabbi Emil William Leipziger led a group in solemn prayer. Still in his early 20s and just a year into his term at reform congregation Temple Israel in Terre Haute, Rabbi Leipziger now presided over the funeral of a Jewish woman barely four years younger than himself.

The rabbi mourned along with a shocked community dealing with tragic loss. And yet, when he said, “Let us repudiate this act of violence,” he did not speak only of the murdered Ida Finkelstein.

He was speaking about a historic, criminal act perpetrated by Terre Haute’s citizens in the lynching of Finkelstein’s accused murderer, a Black man named George Ward.

Rabbi Leipziger experienced a long and illustrious career, culminating in his leadership from 1939-41 of the Central Conference of American Rabbis.

Rabbi Leipziger experienced a long and illustrious career, culminating in his leadership from 1939-41 of the Central Conference of American Rabbis, where he urged social justice, racial justice and gender justice, opening the route for women to become rabbis. He passed away in 1963 at age 85.

It is easy to surmise that Rabbi Leipziger’s experience during the traumatic events of1901 served him in his future calls for social reform.

The Finkelsteins emigrated from Russia

Ida Finkelstein was born March 4, 1880, in Russia, according to census records, to immigrants Solomon and Bessie Finkelstein. The family arrived in the U.S. in 1886. Ida was one of eight surviving children.

In early 1901, 20-year-old Ida taught at Elm Grove School in Otter Creek Township.

Her family had already experienced tragedy in January 1895 when Solomon died, murdered

while working in Sullivan County as a merchant to coal miners. A court sentenced John Ezra to life in prison for the crime.

Solomon’s widow, Bessie, relocated in 1900 to Chicago with four of the family’s eight children and placed three others in an orphanage in Cleveland.

Ida, having recently graduated from high school, decided to remain in Terre Haute to finish her education and begin her career as a teacher. She sent much of her earnings to her mother.

The Max and Theresa Blumberg family offered assistance, and Ida lived with them at 219 S. 5th St. in Terre Haute while she worked and attended school.

An attacker struck as Ida made her way home

Each day, Ida would make her way by streetcar to the eastern edge of the city and walk the remaining five miles to her elementary school. The route to Elm Grove School covered more wooded paths than roads at the time, continuing north and east of the last streetcar stop.

Ida managed to reach the Lost Creek home of Walter Nicholson, just south of the National Road (now Highway 40) about 6:30 p.m., weak and suffering from a loss of blood.

Ida arrived at 9 p.m. at Union Hospital. She died at 11:25 p.m., despite the efforts of three surgeons to save her life.

Dr. Joseph Weinstein arrived an hour later and treated Ida for gunshot wounds to the back of the head and a large laceration across her throat and windpipe. He retrieved a part of the knife broken off in her neck, and called for an ambulance.

Ida arrived at 9 p.m. at Union Hospital. She died at 11:25 p.m., despite the efforts of three surgeons to save her life.

Despite her distress, reports indicate Ida was able to speak and write well enough to describe her attacker as a tall, light-complexioned Black man dressed as a hunter.

Some newspaper accounts alleged robbery, but later reports show Ida still held her money and possessions. Some reports say her person was unmolested while other describe her as beaten from head to foot.

One account indicates Ward, arrested as a suspect, claimed Ida addressed him with derogatory language. The actual text of her written statement has never been publicly cited, nor was her statement disclosed by the police.

Police failed to preserve evidence

Had authorities handled this matter with judicial process, Ida’s deathbed statement would have been preserved and police and courts — and history — could have provided a more accurate account of events. A matching of the knife blade found in the victim’s throat may have helped prove the identity of her attacker. Blood type analysis as evidence was not available in 1901.

And with the tragic death of George Ward within 13 hours of Ida’s passing, police closed the file. The mob took away any hope for justice.

In his eulogy, Rabbi Leipziger grieved Ida Finkelstein and rebuked a society and community that had murdered George Ward.

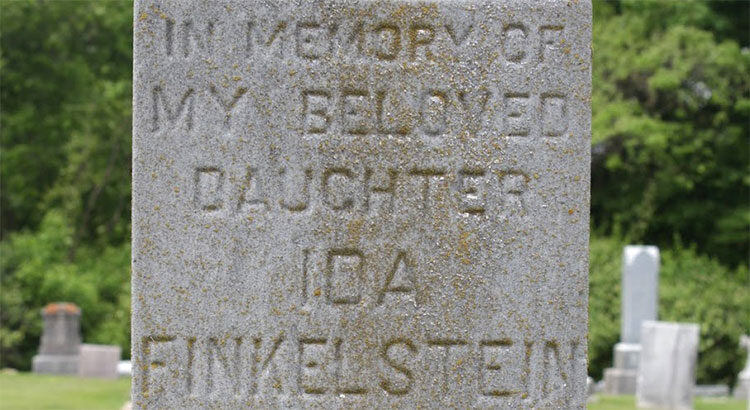

Ida’s mother arrived for her funeral from Chicago, along with two of Ida’s younger brothers, Otto and Roy. Once a large, intact family, they now left Terre Haute with two graves filled at Highland Lawn Cemetery and the household irretrievably split.

In his eulogy, Rabbi Leipziger grieved Ida Finkelstein and rebuked a society and community that had murdered George Ward:

“Let us here, of sober judgment, repudiate an act that has all the weakness of impulsiveness and all the disgrace of impotence.

“Let us repudiate this act of violence, even in our thoughts. We would only desecrate the life of Ida Finkelstein if our love, our sympathy or our respect led us to an impulsive deed.

“Let us repudiate that act of violence! One outrage does not justify another.”